Episode 572

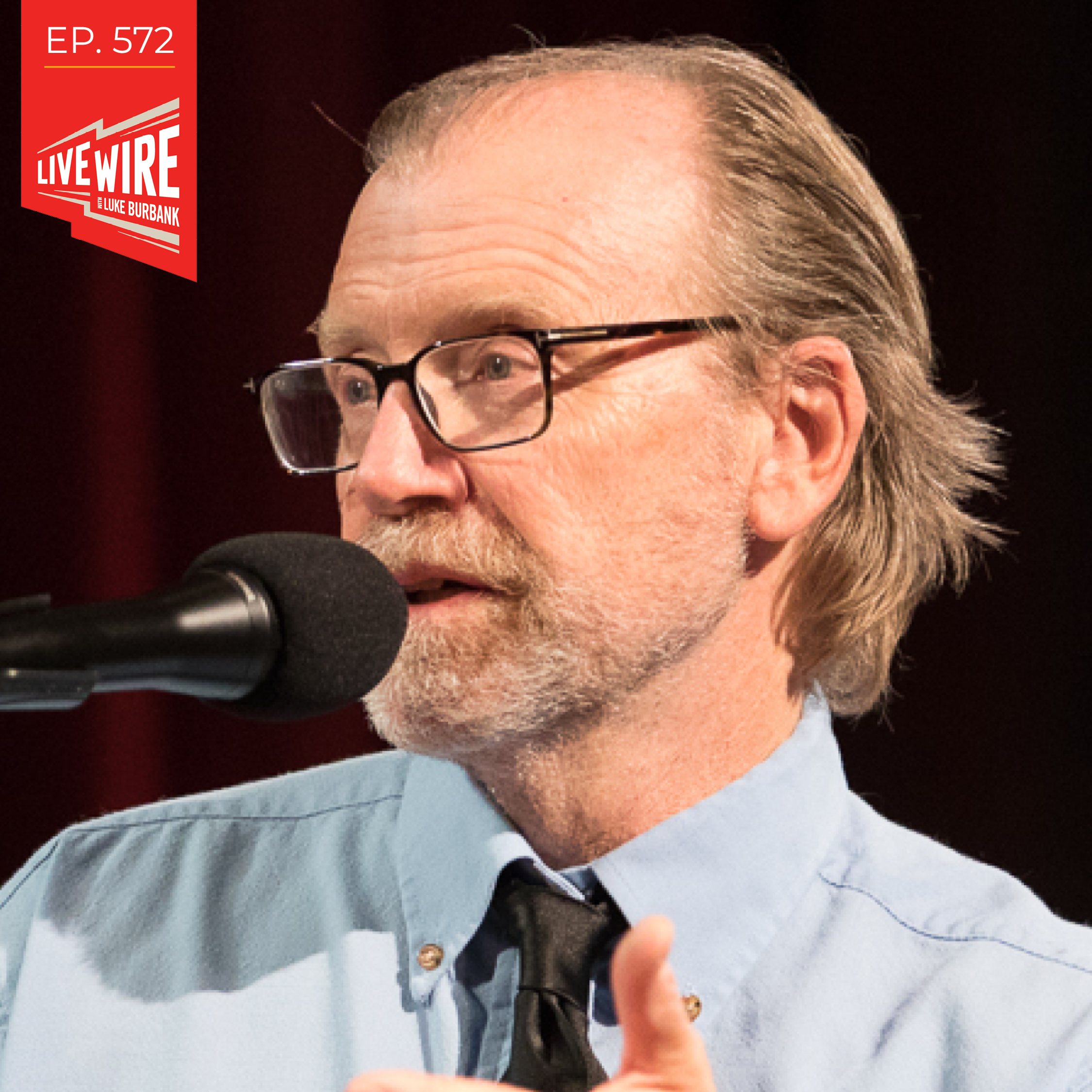

with George Saunders and Samantha Crain

Award-winning author George Saunders (Lincoln in the Bardo) unpacks his writing process and explains how creating confusion often leads to interesting literary worlds; and singer-songwriter Samantha Crain discusses the importance of making music in her Choctaw language, before performing "Joey" from her album A Small Death. Plus, host Luke Burbank and announcer Elena Passarello celebrate teachers and the impact they've had on us.

George Saunders

Award-winning writer and one of Time's "100 most influential people in the world"

The incredible George Saunders returns to the Live Wire stage with Liberation Day: Stories, a brand new short story collection from Penguin Random House. Over his literary career, Saunders has written eleven books, winning both the 2017 Man Booker Prize for his novel Lincoln in the Bardo, the 2018 Audie Award for the book’s audio version, and the 2013 Folio Prize for his other fantastic short story collection Tenth of December. But George Saunders is not just a creative writer, but a man of many talents and he has spent time working as a geophysical inspector in Indonesia, a roofer in Chicago, a doorman in Beverly Hills, and as a technical writer in Rochester. Alongside his litany of fascinating jobs, he is one of Time's "100 Most Influential People in the World" and has appeared on The Colbert Report, Late Night with David Letterman, and NPR's All Things Considered. Currently, he teaches creative writing classes at Syracuse University.

Samantha Crain

Award-winning singer-songwriter

Samantha Crain is a recipient of the Indigenous Music Award and a two-time Native American Music Award winner. Her genre-spanning discography has been critically acclaimed by media outlets such as Rolling Stone, SPIN, Paste, No Depression, NPR, The Guardian, NME, Uncut, and others. Over the past 11 years, Crain has toured both nationally and internationally, and her dynamic shows have showcased both her ambitiously orchestrated musical numbers and her more intimate folk-leaning solo performances.

-

Luke Burbank: Hey, Elena.

Elena Passarello: Hey there, Luke. How's it going?

Luke Burbank: It's going great. Okay. You know how each week we kick the show off with a little thing we call "station location identification examination"?

Elena Passarello: SLIE. Yeah, totally.

Luke Burbank: I love playing this game with you, but I feel like this week is going to be real fish in a barrel territory for you. Because I'm going to tell you about a place in the country where Live Wire is on the radio. You've got to guess where I'm talking about. And I am looking at all of these hints, and I know that you're going to sort of know this immediately. So I'm going to try to start with the most obscure one.

Elena Passarello: Okay.

Luke Burbank: One of the remaining two double barreled cannons that were produced during the American Civil War resides in this city.

Elena Passarello: Well, I don't know anything about where cannons were made. I have no no knowledge of that.

Luke Burbank: Okay. Well, this one, I think, is probably going to be a slam dunk. The band R.E.M. was formed in this place in 1980.

Elena Passarello: The double barrel cannon was made in Athens, Georgia.

Luke Burbank: Yes, indeed. Athens, Georgia, where we are on the radio on WUGA.

Elena Passarello: That's like my old stomps. That's where I used to go. I used to go to Athens is like 35 minutes from where I grew up and, like, sit in coffee shops to be cool.

Luke Burbank: Uhuh. That was my big move in high school as well. Well, shout out to everybody listening to us in Athens, Georgia. All right, Elena, should we get to the show?

Elena Passarello: Let's do it.

Luke Burbank: All right. Take it away.

Elena Passarello: From PRX it's Live Wire. This week, author George Saunders.

George Saunders: I want to avoid the moment where in the graveyard someone goes, Hi, we're ghosts. We're dead, but we don't know it. You know? So in order to kind of keep the naturalism of the story, you have to withhold a little bit.

Elena Passarello: With music from Samantha Crain.

Samantha Crain: I tweeted at Kelly Clarkson and I said, Hey, it's American Indian Heritage Month. You should have me on your show and I'll sing a song in Choctaw.

Elena Passarello: I'm your announcer, Elena Passarello. And now the host of Live Wire, Luke Burbank.

Luke Burbank: Hey, thank you so much, Elena. Thanks to everyone for tuning in from all over the country, including Athens, Georgia. We've got a great show in store this week. Of course, we always ask the Live Wire listeners a question this week in honor of George Saunders, the great writer and also great writing teacher. We asked the audience, what is the most impactful thing a teacher has ever said to you? We're going to hear those responses coming up. First, though, of course, we've got to kick things off with the best news we heard all week this. This is our little reminder at the top of the show that there is some good news happening out there in the world. Elena, what is the best news that you heard all week?

Elena Passarello: Oh, man, I'm going to just tell you right now, I'm going to love every single second of this best news that I'm about to tell you.

Luke Burbank: Okay.

Elena Passarello: It is about one of my favorite things on the planet being used to feed the hungry. So in Greenville, South Carolina, which I believe is home of the radio station where my mother listens to this program.

Luke Burbank: We had a very southern flavor to the show this week.

Elena Passarello: It's all places that I've lived. Anyway, so in Greenville, in a downtown pavilion, 10,000 sandwiches were made in one day by 200 volunteers for local food banks, shelters and schools. It took them 6 hours to make 10,000 sandwiches. But these were special sandwiches because this is Greenville, South Carolina, home to a very special product. These were sandwiches, pimento cheese and bacon sandwiches made with Duke's mayonnaise.

Luke Burbank: Oh, wow. The famous Duke's mayonnaise.

Elena Passarello: So the reason that these were made with Duke's mayonnaise is because Duke's mayonnaise was born in Greenville, South Carolina. And I did not know this about my most beloved condiment, but it was a woman owned business a hundred years ago because Eugenia Duke, who was a stay at home mom, needed to make a little bit of extra money in like 1917. And so she brought her signature sandwiches to nearby Camp Sevier, which was like one of the last places that soldiers would stop of war being shipped overseas to fight in World War One. And she sold her egg salad, chicken salad and pimento cheese sandwiches for $0.10. And they went over like gangbusters at one point in order to help the war effort. She also, with her daughter, made 10,000 sandwiches in a day, which is what I think inspired this great act of charity that happened recently anyway, because her sandwiches went over so well, she decided to bottle and sell the mayonnaise about four years later, meaning that Duke's mayonnaise just had its centenary. And so she had a woman owned business in the 1920s.

Luke Burbank: Oh, that is so cool.

Elena Passarello: And she was super charitable. They held this event where they made all these sandwiches in the very pavilion that used to house the Dukes factory in Greenville, South Carolina, and local Meals on Wheels delivered them. So it was this huge effort. The pictures are really, really gorgeous. And in this article that I read, they also include Eugenie has secret famous recipe for pimento cheese, which I will tell you right now, one cup of shredded sharp cheddar, one cup of shredded white cheddar, third of a cup of Duke's mayonnaise, full stop, quarter cup, diced tomatoes, quarter cup, sweet red peppers and a quarter cup bacon bits. Happy birthday. You don't even need those leftover turkey sandwiches. Just clear out your fridge by a vat of dukes and make this pimento cheese. Oh, by the way, this event that happened where they made these sandwiches used 100 gallons of Duke's mayonnaise.

Luke Burbank: Oh, my gosh.

Elena Passarello: My first thought hearing that was, I just want to swim in it.

Luke Burbank: I'll tell you, like now, all I can think about is having a pimento cheese, bacon and Duke's mayo sandwich. The best news that I saw this week involved a town in Minnesota, Lake Elmo, where the Washington County Library received a book in the mail recently that was 47 years overdue. The person who returned it did so anonymously because they did not want to get in trouble. But they included a note and they said they apologized for having the book for 47 years. They checked this book out in 1975. That was one year before I was born. The book, by the way, was Chilton's Foreign Car Repair Manual. They wrote this letter in the mid-seventies. I was living in Lake Elmo and I was working on an old Mercedes Benz. I took out this book for reference. A few months later, I moved and apparently the book got packed up with the move. Well, 47 years later, I found it in a trunk with other interesting things from the 1970s. It's a little overdue, but I thought you might want it back. And then this person said, My apologies to anyone in Lake Elmo who was working on an old Mercedes Benz in the last 47 years. I probably can't afford the overdue charge, but I will send you enough for a new book. So the borrower also included some money to buy a replacement. So just to kind of like wrap the story up, the person who sent this book and they said that they were worried they wouldn't be able to afford the fines. But like a lot of places, the library in Lake Elmo, Minnesota, has gotten rid of overdue fees for libraries, which I didn't even realize this was a thing that was going on. But it just makes a ton of sense. Like, let's not create any impediments to. People borrowing books from the library. I remember being a kid and being terrified to go check a book out at the Greenlake public library because I knew I owed them money for an Encyclopedia Brown book or two that I hadn't brought back.

Elena Passarello: Is it that an Encyclopedia Brown and The Case of the Overdue Book? I think it is.

Luke Burbank: Yes. I think Bugs Meany and the Tigers probably were up to no good involving an overdue life.

Elena Passarello: That villain Bugs Meany.

Luke Burbank: That's right. All right. Anyway, the Lake Elmo Library getting its full collection back is the best news that I heard all week.

Luke Burbank: All right. Let's welcome our first guest on over to the show. He's one of our favorites. And it's got to be one of the few people who was a one time Chicago roofer, Beverly Hills doorman, and also a winner of a MacArthur Genius Award. He's written 11 books, the novel Lincoln in the Bardo, which he wrote, won the Booker Prize. TIME calls his latest collection of stories, Liberation Day, an exquisite work from a writer whose reach is galactic. Take a listen to this. It's our interview with George Saunders, recorded at the Alberta Rose Theater in Portland.

Luke Burbank: Hey, George, welcome back to the show.

George Saunders: Nice to be here.

Luke Burbank: This book is a really amazing-- Liberation Day. I'm curious. Did you know you were writing a book at the time or were you just writing short stories?

George Saunders: It's kind of the same for me. Like, I just the default mode is writing stories. That's what I always do. So then you start seeing them sort of add up and I go, that's that's 80 pages. That's almost a book, you know? If I just use a bigger font where pretty much there.

Elena Passarello: Like the readers print Reader's Digest, large print.

George Saunders: Well, the condense books. Remember the Reader's Digest condensed books. Yeah, those were pathetic. What was that about?

Luke Burbank: They're like whole sections of the Count of Montecristo I don't even know about because I read the book version. I know it's about a sandwich....

George Saunders: Or that whole book or Scrooge is only nice. That was a trip.

Luke Burbank: I'm always very curious about a writer's process, and I know you get asked about this a lot, but do you have an idea of like, Hey, what if these people were being kept as like human machinery in order to...

George Saunders: That's the only idea I have, actually

Luke Burbank: Thank God it made it into the book. No, you had you have an idea of some very sort of interesting scenario and then you kind of work out from there.

George Saunders: No, it's really more an attempt to not have any ideas. Like if I have a thematic idea, then I just do that, you know? And there's this thing I quote from Einstein all the time it's no worthy problem is ever solved in the plane of its original conception. So if you just do what you set out to do, it's a buzz kill. It's that that's no fun. And the reader feels like she's just kind of the passive victim of your big idea. Whereas if it's like being on a date, ladies, you know.

Luke Burbank: But I believe that's called my first two marriage.

George Saunders: But if you can get as a writer, if you can get yourself a little bit interested and confused, which I usually do just by making up some crazy voice and I don't even know where it's coming from. I'm just trying to do it for two or three pages. Then at some point you go, Okay, why is this person talking so weird? Which then equals worldbuilding? So the whole thing to me is to be a little bit happily, openly confused. Then the reader kind of is like, Well, he seems confused. It's like when you're on a bus being driven by a drunk, you know, like, oh, everybody's are we okay, you know?

Luke Burbank: But do you feel like that's a relatable experience?

George Saunders: Oh, yeah. Yeah. But the whole thing is, is if I if I as a writer, am keeping the reader in mind by not being too sure what I'm doing and sort of admitting over my shoulder like I'm a little lost right now, but bear with me then. The idea is that the reader at least feels involved. So there's like an intimate communication going on, and then you just go where the story goes for like four years.

Elena Passarello: And does that get harder and harder the more often you land on a short story that's successful? Right. Like when you're on your 50th successful short story to to actually shake yourself up?

George Saunders: It is because, you know, you find out, especially if you're me, that there's a very narrow wedge of talent. Actually, that's not infinite. Like some or no, some writers can write anything, and I'm not one of those. So you end up kind of like trying to find a square centimeter you haven't done before, or sometimes you'll have a story that is actually fairly similar to one you've written before, and then the game is okay. I have to find a new a new valence, I have to find another twist. So, yeah, it's it's a challenge for sure.

Luke Burbank: Do you have a sort of internal clock or something that you're following as to when it's time to start revealing in the story? Because I have sometimes have the experience reading your stories and now I know it's by design where I have a no idea what's going on at first. Why are these people saying this? Are these people what is happening? Right. Right. And then like writers, I'm about to like go to the next chapter. Something just turns as a little piece of information is revealed. And now I'm like, really invested. How do you know when to do that?

George Saunders: And it's it's really through revision. And so I always talk about this imaginary meter in your head as a writer. So this is positive. This is negative. So as you're rereading your work, you're kind of you're reading it, trying to be a first time reader, and you're watching that meter and you're seeing, well, would I still be into be into this? You know, this guy being too smart for his own good. Are there too many jokes? Is the reader pleasurably lost or just getting pissed off, you know, that you know? And then and then as you're going through it, if you feel like, yeah, I'm being a little bit too obtuse, you drop in a little clue, you know. So the whole thing for me is mostly about, for example, Lincoln in the Bardo. A lot of people I had this experience when I was touring that book. I see how many people made it past page 30 and about half the room would raise their hand, you know, so. So it's got a kind of a difficult beginning. But that was because I wanted to avoid the moment where in the graveyard, someone goes, Hi, we're ghosts. We're dead, but we don't know it. You know, that's a violation of the contract, you know, because they don't know that. So in order to kind of keep the naturalism of the story, you have to withhold a little bit. But again, not too much so. It's kind of like like I guess in high school, that titration, you know, like you read it through one time and you're keeping the reader out, okay, you got to change that. And it's over and over again, many, many iterations. Yeah.

Luke Burbank: We need to take a very quick break here on Live Wire. We were talking to George Saunders. His new collection of short stories is Liberation Day. We're here as part of the Portland Book Festival, and we will be back in just a moment.

Luke Burbank: Welcome back to Live Wire from PRX. We're talking to George Saunders this week, part of the Portland Book Festival. Your book, Lincoln in the Bardo deals with people that are kind of in between life and death or post-death and before whatever else happens. There are characters in this book, Liberation Day, that are also in that state for various degrees of time. Do you think about death a lot like as a person, is it a big topic for you? Your normal life?

George Saunders: Oh yea, everyday. No. Yeah. No, I do. Even as a kid, I was kind of kind of death obsessed somehow. But I think only because it's just weird, you know, that you get up, you put on a tie. This is a tie and a corpse. That's weird. You know, so. So the idea that we have in this life. This life. In this life, you have this incredible urge to love and be loved. That's that's the strongest thing. And then you realize everything that you love is conditional. So. So how do you, you know, live a functional life where everything tells you to love and that's natural, and at the same time, everything is going to go away, you know? So it's to me, it seems like this the real question of any literature is how do you make a functional life out of that dichotomy, you know? So, yeah, it's cheerful. Certainly it's cheerful. You know.

Luke Burbank: You teach this writing program at Syracuse that's quite revered and, you know, only lets in a kind of short list of students every year. I'm curious, your teach storytelling there, like, is it sometimes stressful for you to write stories and have those students read because you're the person at the front of the class going like, this is how you do it, right? And now you're like, you're teaching trumpet. And then I was like, And now here's how it should sound.

George Saunders: Yeah, it's actually it's sort of the opposite. They they are so good. We get 700 applications and we pick six people. Yeah. So they're amazing. But it's kind of a fountain of youth because if you ever, you know, as one tends to do, as you get older, you get a little cynical, you know, it's all downhill after Foghat, you know, that kind of thing. But but seriously, do you get in in a room with these six young people and you see the talent is eternal. It never goes away. It changes flavor, of course. But so it's really kind of an anti cynicism recipe to sit down with them and realize that you have to really bring it every time and in in the stories that you teach and hopefully in your own work. So it's been it's been really a lovely life for my teaching.

Luke Burbank: But I mean, after you've told them these are the principles of, of, of good storytelling and this is how you write and then you write a thing and then it's out in the world and they're reading it. Do you ever feel like you've a hard time living up to what you're teaching in the class?

George Saunders: I think they don't read them. I mean, I don't hear a lot about it. And, you know. Yeah. No. And also but honestly, you know, one of the best thing that ever happened when I was a students, one of our teachers got a kind of a bad review in the Times, and we were all very nervous about it. And then we went in the class and he just said, let's talk about this, you know, fearless. And he said, there's some merit in this. Some of this argument is incoherent. Some of it is. And he said, you know what I'm going to do tomorrow? I'm going to write another book, you know. So the fact that he would be so honest with us and open up like that was really good. And it made us realize that, you know, you're theoretically doing it for something more than reviews. You're doing it for the long the long game. You're doing it to find something in yourself. So that was really inspiring, you know. So yeah. Yeah.

Luke Burbank: We're talking to George Saunders here on Live Wire this week, part of the Portland Book Festival. George's latest book is Liberation Day. I don't know. I am I'm I'm unusually obsessed with this detail of your life, which is that you graduated from the Colorado School of Mines and that you lived like up a pretty substantial adult life that wasn't as a writer before you got into writing. I think that really grounds a lot of the stuff that you do. Or maybe just because I grew up in kind of a like a blue collar background, I didn't like associate with that. I'm wondering, though, now that you are mostly in the classroom and are mostly coming to book conferences and interviews and doing Stephen Colbert next week, like, is it hard for you to stay connected to whatever it was about your early life that helped you really know what it's like for normal people?

George Saunders: Maybe a little bit. I think a lot of that stuff, if it if it hits you early, it stays in the DNA a little bit. So I think, yeah, it's kind of I remember working at the slaughterhouse, you know, and getting up in the morning and your hands would be frozen shut, you know, and I was 25 or something and hands are shut and you have to run hot water on them to open them up, you know, so that kind of stuff, you kind of and I still flinch whenever I use a credit card like, you know, oh, it worked, you know. So but I do. But I think, too, that, you know, in a certain way. Okay, so if you're lucky enough, as I've been to maybe not have to worry so much about that, then the habit of worry can be put to good use, which is to say life in general is full of hard knocks and suffering. And people, people it's like, as Tolstoy said, it's hard down here brother, you know. So I think once you've had a taste of that in your own life, you can kind of look up and see, yeah, you know, it's never easy here. And the last few years, so difficult, you know. So then fiction. At least as I understand it can be a way of just reaching out to someone and saying, I know it's hard, or if it's not hard now, I know it's going to get hard. We're all together, you know, that kind of thing. But also that beautiful process of starting a story, let's say in my story stories, often the character at the beginning is kind of played for a bit of a joke. There's often a little first sections where the reader and I are kind of going, Look at that weirdo. That's funny, you know? You know somebody like that? Yeah. No. And then that because the story can't stay static. I have to go back in the second beat and look at her again. And I have to say to her, basically, is there anything you'd like to tell me about yourself? And they always do. You know, the characters do in revision. So then suddenly you have somebody that you maybe made a little bit of fun of, and then you find out something that's going badly for her. Your sympathy gets engaged. You see that your first facile opinion was a little bit too easy, and this goes on and on. So by the end of it, ideally the reader and writer together have gone through this process of being shorn of too easy judgment. You know, and so for like 10 seconds at the end of the story, like, oh, God, I could be that open minded always or that affectionate always. Then of course, you go back to normal, but in essence, it's gone. But in essence, it's kind of Sacramento because you go, Oh, I remember I had a glimpse of a better version of me at the end of that Chekhov story. You know, you could get there again, maybe.

Luke Burbank: I got a text this week from a friend of mine who hosts the show. Wait, Wait, Don't Tell Me. Peter. Peter Segal, who interviewed you at the Chicago Humanities Festival. And he sent me all the questions that he didn't get to. With you. And this is one of them. But I want to preface it by saying this was his question. Oh, do you think there is something wrong with ending a story in a happy way?

George Saunders: No, no. You know, I think he just chickened out. I think, you know, no, there isn't. But only if it's earned. You know, if this story, you know, you you're revising it and you're leaving all kinds of hints about the reality of the story. If you get to the end and you have to falsify to make it happy, that's not happy. That's the worst kind of darkness. That's that's the Hollywood movie. You know, where everything goes well, in spite of what the preceding 3 hours or 2 hours said. So to me, the happy story is a one that's true to itself and the one where the reader and writer get to put their heads together and say, Let's look at this made up person and look at let's just be honest about it. Let's both bring our experience. Let's look at it honestly. Then, even if it's a, you know, quote unquote, sad ending, you're still uplifted by that. By that. I mean, Flannery O'Connor, she doesn't have a lot of like lottery wins at the end of her show, you know, but but every time I read her, I feel more alive. I feel more realistic. I feel actually more fond of people, even ones that I might not have liked before. So but I'll work on it.

Luke Burbank: Talk to Peter

George Saunders: Now, I think in this book there's a story called Sparrow that I think has a very happy ending in this book, you know? So that's one.

Luke Burbank: And, you know, maybe because it's tonally a little different than the other pieces in the book. I've never been rooting harder for two people at a grocery store to find love. So there you go.

George Saunders: Yeah.

Luke Burbank: A lot of this this latest book, Liberation Day, feels to me like it's written from the other side of the sort of collapse of life as we know it here. And I'm wondering if you feel like that is inevitable. I wanted to kind of wrap things up on sort of a softball.

George Saunders: Yeah. I mean, eventually it's inevitable, but I don't think it's I don't know. I actually think, you know, people who still believe in hope and love and equality and all the things that the country is supposed to be about. We have a lot of energy in a system that is based on fear and demonizing the other and hopelessness that that system won't last. So I think whatever happens, we're going to be okay because there's a lot of people in this country who who believe in what as it's supposed to be. So it might be uncomfortable and it's going to be I'm sure it's going to spin could spin out of control in ways that we don't see. But I think I think, you know, for as a lifetime progressive, somewhat left of Gandhi, I think it's an important moment for people who feel that way. It's not to despair and to say, no, we know what the country is about and it's our country, too, and we're going to stand up for it.

George Saunders: You are listening to Live Wire from PRX. We're here talking to George Saunders about his latest book, Liberation Day. As we've already discussed, along with being a celebrated writer, you're also a celebrated teacher of writing at Syracuse University. And as it happens, are announcer Elena Passarello is also a professor of creative writing. And well, in fact, a lot of your MFA students are here with us.

Elena Passarello: You made it. Good. Good, good.

George Saunders: They all got A's.

Luke Burbank: And I understand that they have submitted some actual questions for George Saunders.

Elena Passarello: Yes.

Luke Burbank: So we've got about five of these questions in a jar here. And we're going to...

Elena Passarello: Tell you what I going to call it. Yeah, the MFA AMA.

Luke Burbank: That's pretty good

Elena Passarello: Right.

Luke Burbank: We call this exercise the MFA AMA

Elena Passarello: But it doesn't go with the sting.

Luke Burbank: So how this is going to work, George, is we'll have you select a question from the jar of truth. These are written by actual MFA students of Elena Passarello. Elena will read you the question and then you will give us your best answer. So if you want to hand it to Elena, she will read it to you.

Elena Passarello: Oh, okay. So this is from Jonas, second year fiction writer, good friend of the show. What is the best non-writing activity that you can do to become a better writer?

George Saunders: Reading. Reading, really.I mean, really. That's it? Yeah. Yeah. I mean, I think you're always I tell my students, you have to imagine you have this silo over your head and you're putting all kinds of stuff in the Russian stories, analysis of stories, your life, everything. And then you trust that all that stuff is going to work its way into your artistic body. And it has some moment of intuition. It's going to help you. It's not that you're consciously doing it, but it just makes you a richer, fuller person.

Elena Passarello: I was really hoping you were going to say drinking. Yeah. Well, we'll take this. We'll take that as well.

Luke Burbank: I would be Hemingway if that were the solution. All right, George, can you please select another question from the MFA AMA Project?

Elena Passarello: Thank you for you humoring me.

Elena Passarello: Okay, so this is from Jocelyn first, your fiction student. How do you know if a story idea is worthwhile? How long does it take until, you know? This is several questions. What happens to the rejects? Do they ever or often show up again in other form?

George Saunders: Yeah, no, that's a great that's a great writerly question, I think. My my assumption is you if it comes to you without a lot of attachment and concepts and stuff, then and you feel interested and then it's a good idea and then you've got to wait, you know, you've got to really wait for it to do that thing where it comes out of the plane of its original conception. And so that's a kind of an act of faith. But what it means is as you're working along, if you get locked up, that's your story saying to you, you're underestimating me, you know? And then you say, What do you mean, little story? And it says, You think you know what I'm about? I don't mean to hurt your feelings. You are hurting my feelings. So. And then. But. But you wait. You wait. You wait it out. And and then in time, it'll start to lead you, you know. So I think for me, it's you pretty much just assume it's a good idea and that anything that looks like an obstruction, you know, or a goiter or a mistake is actually this story's way of leading you to higher ground.

Elena Passarello: You know, have you ever invented, like, a really great character and then not been able to figure out where to put them for more than a month?

George Saunders: Yeah. It what happened in this book. There was a story called 10th of December and there was a mother character in there and I wrote the scene was pretty funny and it just wasn't needed. So, you know, with great pain, I plucked it out and put it in a file and then I just left it there. And then a couple of years ago, I used it to make that mama bold action, you know, and it's funny because that woman didn't want to be in that story. It's like, I don't belong in here. I don't care about this one. You take you take her out, and it's almost like a flower that gets in the right pot. She's like, Oh, this is more like it. Now, let me tell you the story I want to tell you. You know, so.

Elena Passarello: Yeah, that's amazing.

George Saunders: Yeah.

Luke Burbank: Okay. A couple more questions, please, from the jar of truth while we have you also, this does count as credit at Syracuse University gives program to everyone here at the Alberta Rose Theater.

Elena Passarello: Okay, how about this one from nonfiction MFA student Emily. In an interview, the nonfiction writer does the research. In an interview, you said the best writing advice you ever received was from Tobias Wolff, who said, Don't lose the magic. Great. How do we keep the magic?

George Saunders: Yeah, well, totally. I was I had been a funny writer when I came to Syracuse. And then I got tight seat tight below the waist. I wouldn't want to use a bad word on your radio show, but things down there were suddenly stiff. Yeah. That sounds like I'm bragging. Yes. I should have said tight ass. Well, it's something about being on the radio. I become very serious and. No, no humor. And so I saw Toby at a party, and I said, I just want you to know, thank you for letting me in. But from now on, this funny stuff, no more, it's going to be real literature. And he just looked at me over his glasses. Well, good. Just don't lose the magic. And I was like to myself, Why would I do that? Of course not. And then I went off for six years and just kept writing serious sort of Hemingway imitations. And so then when I finally was, you know, became funny again, that that advice just flashed in my mind, like, of course, you idiot, you know? So I think I think what I tell my students is that magic just means you're writing in a way about which you have strong opinions, not strong intellectual opinions, but visceral opinions. Like I always knew what it was like to be funny and when it wasn't, I always used funny in my life to get in, to get out of trouble or whatever. I had a first girlfriend who broke up with me because I told too many jokes and then I told a joke without even, you know. So she continued to break up with me. But but so then to say. But then when I started writing funny, I always knew, you know, I had a strong opinion. So I think if a student writes and then when she rereads the work, she has really strong, visceral opinions about it. She's probably on the right track.

Elena Passarello: It sounds like you have to like just constantly know yourself in some kind of way as you grow and change and you. It's not even like you have to keep your writing sharp of course that's true. But you have to keep your like your self awareness or your self. Is that is too much to ask?

George Saunders: I think well, I mean, that's kind of I think the mindset you're in when you're revising is you're just saying, what, I like this if I hadn't read it before. Is it exciting? Does it does it throw me? And I think that since so much of writing is actually reacting to what you've already done, you can kind of do that. You don't have to have a big thought about it. You can just read it and see what you feel like doing. And I think the feel like that phrase is really important, you know, should be fun. If writing isn't fun, I don't think it's even if it's very serious, it should still be fun to do it in some. Otherwise, how do you know, you know, what's the guidance? How do you know where to go?

Elena Passarello: And even when you're writing really dark, there's still an element of fun. That's a part of it.

George Saunders: 100%, yeah. Yeah. Because, you know, like, no actual humans are harmed. You know? You know, I mean. They're just symbols. And and really you're saying, okay, what if, you know, a part of a house fell on Cliff and crushed him? Well, there's no Cliff, so it's all right, you know. But then you can say, yeah, okay, let's start with that. And then we're going to see, you know, what Cliff is like there on the ground and we're going to see by association what human beings are like under duress, you know, so it's all kind of a a game, really, you know. Yeah.

Luke Burbank: George Saunders Everyone right here on Live Wire.

Luke Burbank: That was George Saunders recorded at the Alberta Rose Theater in Portland, Oregon, as part of the Portland Book Festival and George's new collection of short stories. Liberation Day is out now.

Luke Burbank: Live Wire is brought to you in part by Alaska Airlines. Alaska Airlines offers the most nonstop from the West Coast, including destinations like Hawaii, Palm Springs and San Francisco. And as a member of the OneWorld Alliance, Alaska Airlines can connect you to more than 1000 destinations worldwide with their global partners. Learn more at Alaska Air dot com.

Luke Burbank: This is Live Wire Radio as we do each week. We asked listeners a question because we have been talking to George Saunders, who is also a great teacher of writing, and also because Elena Passarello is a great teacher of writing. We wanted to find out what the most impactful thing a teacher has ever said to our listener. Folks have been sending in those responses. Elena has been collecting them up. What do you see?

Elena Passarello: Ellie says, My second grade teacher once said, You play stupid games, you win stupid prizes. It really makes you think.

Luke Burbank: Certainly stuck with her. I was perpetually in trouble in school, which will come as no surprise to the listeners. And I used to get detention all the time, and I would sit in third grade class during recess, and I would stare at my teacher, Mrs. Wharton, and she would eat an apple slowly, and then she would consume the entire core while maintaining unbroken eye contact with me. That wasn't so much verbal, but it really stuck with me.

Elena Passarello: That was your stupid prize for playing stupid game.

Luke Burbank: That was exactly. What's something else memorable a teacher said to one of our listeners?

Elena Passarello: Here's a wonderful one from Lisa. Lisa says, At my eighth grade graduation, my teacher told me he wanted an invitation to my college graduation, and I never forgot that. That's so important, I think, for a lot of students to be told that someone sees the future for them. Like it's I think a lot of people take it for granted because they've had adults their entire life telling them about their future. But sometimes school is the place where where adults help students really visualize a longer path to bigger goals. Goosebumps all over just reading that one.

Luke Burbank: Absolutely. You know, I was the first person in my family to go to college. I don't think it even occurred to me. And I had a an English teacher at Nathan Hill High School who said, hey, you should go to college. And I think that was part of why I actually did it. So yeah, it's amazing the impact one adult kind of looking out for you can really have.

Elena Passarello: Yeah, it's a good thing to keep in mind.

Luke Burbank: What's another piece of advice that a teacher gave one of our listeners?

Elena Passarello: This is a touching story from Kathleen. Kathleen says, The most impactful thing a teacher ever told me was that I was the most social person she'd ever met because she had a student who will call David, who ate his lunch in her room alone every day. But I had her class after lunch, so I'd always come in and say hi to David and he would light up. She complimented me and said, There are probably days when I am the only person who talks to David all day to say his name. And it's a lesson I've always carried with me that maybe being uncool, which is very important to high schoolers, was worth it if it meant making someone feel that they belong.

Luke Burbank: Wow. I really wish we could all go back to high school as, like, 40 year olds, because I feel like you just become such a more aware person and probably a more at least I'm a much more, I think, empathetic person at my age. I would be going around the school talking to all of the Davids if I knew then what I know now about sort of how humans are, you know.

Elena Passarello: And what mattered. I think sometimes in high school, like the wrong things or the things that don't actually matter matter, but that kind of stuff, like seeing people and being with people that matters.

Luke Burbank: Well, shout out to all the teachers who got mentioned today for saying really important stuff to their students. We really appreciate what you all are doing out there, and we appreciate everyone who sent in their responses to the question. Thank you.

Luke Burbank: You are listening to Live Wire Radio. I'm Luke Burbank. Right over there is Elena Passarello. Okay. Our musical guest this week is a two time Native American Music Award winner. Her genre spanning discography, which she likes to refer to as y'allternative, has been critically acclaimed by the likes of Rolling Stone, Spin, The Guardian and NPR, who ranks her latest album, A Small Death, as one of the 50 best albums of 2020. Her latest EP is called I Guess We Live Here Now. Take a listen to Samantha Crain here on Live Wire.

Luke Burbank: We had you on the show before, but it was in the pandemic. And so it was kind of virtual, if I remember right. Were you at the airport on your way to a show that we were going to have that got canceled or.

Samantha Crain: Oh, yeah. I was actually I forgot about that. It was right at the beginning of the pandemic. And I, I was in London and they were like, they're closing the borders, so you should go back to the States. And so I did. I was trying to get here to do the show. I forgot that that was the beginning.

Luke Burbank: I'm glad that was something that you forgot.

Samantha Crain: That was you guys. You did that.

Luke Burbank: We cancelled like the day you are going to fly here. I understand that you played the Kennedy Center recently and you sang in Choctaw.

Samantha Crain: Yeah. So I started writing songs in Choctaw a few years ago, and I did perform one of those songs at the Kennedy Center. I think I just started doing it because, you know, I grew up hearing the language in powwow songs or in sort of traditional songs in terms of like Christian hymns that had been like translated to Choctaw or something like that. But I, I think I was just sort of thinking, you know, this is like a living, breathing language. Like there's people that still speak it. I speak it. There's like young indigenous people that want to utilize the language in their own creation. And so if we are modern, contemporary people, why not make. I'm a songwriter, I'm Choctaw. So this is sort of my job, right? Like make modern contemporary songs with modern contemporary thoughts and feelings in use the language. So it's a slow process for me because it's like a second language, but I am trying to like get at least one song on every album from, from now on.

Luke Burbank: And which you're trying to get. Is it Kelly Clarkson?

Samantha Crain: That was a joke. I was drunk the other night.

Luke Burbank: Yeah, I was ready to mobilize the Live Wire listening audience to make this happen. You tweeted at Kelly Clarkson saying you want to perform a song in Choctaw on her show because it's Indigenous Peoples Month?

Samantha Crain: I did, yeah. It's American Indian Heritage Month. And I was watching Love Is Blind the other night and I had had like a bottle of wine and I saw like a commercial for like the Kelly Clarkson show. For some reason, I don't know. Or maybe I was just like doing the phone doomscrolling or something, and I was like, I've got an idea.

Luke Burbank: I think it's a good idea. I think we should try to make it happen.

Samantha Crain: So yeah. I did. I tweeted at Kelly Clarkson and I said, Hey, it's American Indian Heritage Month. You should have me on your show and I'll sing a song in Choctaw. And I and I think I only got like five retweets, so.

Luke Burbank: I'm going to retweet it right now, which should get that up to like seven, eight.

Luke Burbank: This is Live Wire. I'm Luke Burbank here with Elena Passarello. We are listening to our conversation with the musician, Samantha Crain. Now we've got to take a quick break, but don't go anywhere. We are going to be back with some music from Samantha that is absolutely going to blow your mind. So stick around. More Live Wire in a moment.

Luke Burbank: Welcome back to Live Wire from PRX. I'm Luke Burbank, here with Elena Passarello. We are listening to a conversation we had with the singer and songwriter Samantha Crain at the Alberta Rose Theater in Portland, Oregon. Check it out. I know that you've had some music featured on what I think is one of the coolest. It's not even new because they're going to season three, but Reservation Dogs, which is shot in Oklahoma where you're from. That show is so good.

Samantha Crain: It's so amazing. And like the amount of pride that people from Oklahoma have for it, especially if you're like native and from Oklahoma, it's like a double. And Sterlin Harjo, the creator and sort of showrunner for the show with Taika. Sterlin is like one of my best friends. We've been working together since I was like 18, basically. So I've had music like in a few of his films and he'd made like early music videos for me and all this. So it's like so amazing to see him take all of these ideas that I've seen him have over them. That was like 15 years and finally get like the TV show to put all of the good ideas in it. And then, yeah, luckily I'm getting to do some music for it too. So yeah, the show is so good.

Luke Burbank: Obviously it's a television show, so things are played for... Everything is heightened because that's how it works on TV. Do you feel, though, that that is on some level a fairly accurate representation of of your experience being Native American in Oklahoma?

Samantha Crain: Yeah, I think so. I mean, obviously, that show is shot a bit more in like a like a slightly like you said, slightly heightened...

Luke Burbank: But you didn't steal a Flamin Hot Cheetos truck with your friends.

Samantha Crain: No, I did not

Luke Burbank: To sell at a scrapyard.

Samantha Crain: I did not. But there are there are definitely like elements of the storylines of those people that match up with my life or with people in my family or friends of mine. And I think beyond that, just the the humor of it is very like location specific and also very like culturally specific, too, which is that's what's so funny about it to me is that people think it's funny outside of like Oklahoma and Native communities in Oklahoma. Because I just thought it was so like culturally specific to us.

Elena Passarello: It's super inside baseball.

Samantha Crain: Like everything. I'm just like, Oh, it's an inside joke. You wouldn't get it. And then they're laughing. So I didn't know that.

Luke Burbank: Somebody saying, Go get White Dave is always funny, I think in any context.

Samantha Crain: Yes, yes. Yes.

Luke Burbank: Okay. Can we hear a song?

Samantha Crain: I'm going to play a song called Joey, which is actually I think it's on the pilot episode of Reservation Dogs. If it's not the pilot episode, it's the second episode. Okay. So it kind of fits with this good transition. I didn't even plan this.

Luke Burbank: Oh, this is serendipity.

[Joey by Samantha Crain Plays]

Luke Burbank: That was Samantha Crain right here on Live Wire. Her latest EP, I Guess We Live Here Now, is available now. All right. Before we get out of here, a little preview of next week's episode. Okay. We are going to be talking to John Darnielle. You might know him as the lead singer of the band The Mountain Goats. He is also, though, it turns out, a very talented novelist. He's a New York Times best seller. And we're going to talk about his latest book titled Devil House and his complicated relationship with the True Crime Genre. Then we're going to chat with the rapper and writer Dessa, who will also tell us about the challenges of heading back out on tour post-pandemic, and how she channels her passion for behavioral science into her podcast, Deeply Human. She's one of those rappers who hosts a podcast about human behavior. And as always, we're going to be looking to get your answer to our listener question, Elena. What are we asking the listeners for next week's show?

Elena Passarello: We want to know what is something you have expertize in that people would be surprised by.

Luke Burbank: Okay. If you have got a thought on that, if you like to send us your response. You can always go on Twitter or Facebook. We are at Live Wire Radio out there on most of the social media. All right. That's going to do it for this week's episode of the show. A huge thanks to our guests, George Saunders and Samantha Crane. Also, special thanks to the Portland Book Festival. Live Wire is brought to you in part by Alaska Airlines.

Elena Passarello: Laura Hadden is our executive producer, Heather Dee. Michelle is our executive director. Our producer and editor is Melanie Sevcenko. Our assistant editor is Trey Hester. Our marketing manager is Paige Thomas and our production fellow is Tanvi Kumar. Our house band is Ethan Fox, Tucker, Sam Tucker, Al Alves and A. Walker Spring, who also composes our music. Molly Pettit is our technical director and mixer and our house sound is by Neil Blake.

Luke Burbank: Additional funding provided by the Oregon Arts Commission, a state agency funded by the state of Oregon and the National Endowment for the Arts. Live Wire was created by Robin Tenenbaum and Kate Sokoloff. This week we'd like to thank members Matthew Smedley of Melbourne, Australia. Day Matthew. And also apologies for that very tired day. For more information about the show or how you can listen to our podcast, head on over to Live Wire Radio Dawg. I'm Luke Burbank for Elena Passarello and the whole Live Wire crew. Thanks for listening and we will see you next week.

Elena Passarello: PRX.